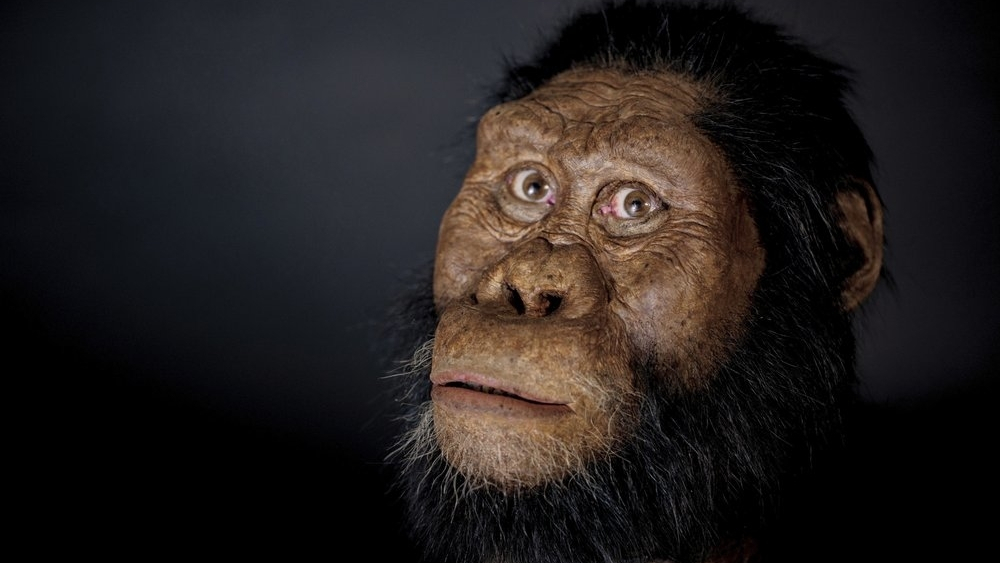

This undated photo provided by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in August 2019 shows a facial reconstruction model by John Gurche made from a fossilized cranium of Australopithecus anamensis. /AP Photo

A 3.8-million-year-old, rare and fairly complete hominin skull discovered in Ethiopia could change what we know about the origins of one of human beings’ most famous ancestors, Lucy.

Lucy, the celebrated Ethiopian partial skeleton was found in 1974.

This latest discovery, uncovered in 2016, is the oldest known member of Australopithecus anamensis, a grouping of creatures that preceded our own branch of the family tree, called Homo.

Scientists have long known that A. anamensis — existed, and previous fossils of it extend back to 4.2 million years ago. This species was thought to precede Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis. But features of the latest find now suggest that A. anamensis shared the prehistoric Ethiopian landscape with Lucy’s species, for at least 100,000 years, the researchers say. This hints that the early hominin evolutionary tree was more complicated than scientists had thought.

This undated photo provided by the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in August 2019 shows a fossilized cranium of Australopithecus anamensis. The species is considered to be an ancestor of A. afarensis, represented by “Lucy” found in 1974. From 3.8 million years ago, the ancestral species is the oldest known member of Australopithecus, the grouping of creatures that preceded our own branch of the family tree, called Homo.

The newly reported fossil includes much of the skull and face and apparently came from a male. Its middle and lower parts jut forward, while Lucy’s species shows a flatter mid-face, a step toward humans’ flat faces. The fossil also shows the beginning of the massive and robust faces found in Australopithecus, built to withstand strains from chewing tough food, researchers said.

“What we’ve known about Australopithecus anamensis so far was limited to isolated jaw fragments and teeth.” study co-author Yohannes Haile-Selassie, a paleoanthropologist at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, told reporters during a news conference announcing the find. “We didn’t have any remains of the face or the cranium except for one small fragment near the ear region.”

Experts unconnected to the new study praised the work. Eric Delson of Lehman College in New York called the fossil “beautiful” and said the researchers did an impressive job of reconstructing it digitally to help determine its place in the evolutionary tree.

William Kimbel, who directs the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, said the discovery helps fill a critical gap in information on the earliest evolution of the Australopithecus group.

The study’s authors said the finding indicates A. anamensis hung around for at least 100,000 years after producing Lucy’s species, A. afarensis. That contradicts the widely accepted idea that there was no such overlap, they wrote.

Scientists care about overlap because its presence or absence can indicate the process by which one species gave rise to another. The paper’s argument for overlap rests on its conclusion that a forehead bone previously found in Ethiopia belongs to Lucy’s species.

But several experts, including Kimbel, were not convinced that conclusion is correct. So the question of just how Lucy’s species arose from the older one remains open, Kimbel said in an email.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3